THROUGHOUT the spring and summer of 1955, small bands of men worked feverishly against the clock in London. They had a deadline to meet — September 22, 1955 — the night they must open a new television service in Britain.

Only the London area would see the new programmes to begin with — the rest of the country would follow at gradual intervals.

Two companies had been awarded programme contracts by the Independent Television Authority to provide the London service. They were Associated-Rediffusion, who had to provide the Monday-Friday weekday programmes; and Associated Television who had to provide programmes at weekends.

Independent Television News, whose job was to provide a news service had been established and Associated-Rediffusion had undertaken the publication of TV Times for the whole ITV network.

The men at the top of these companies started with almost nothing but their own determination and energies. They had no staff, no permanent office premises, no studios, no cameras, no sound equipment. And they had only 11 months altogether, from the date of the announcement that they had been awarded programme contracts in October, 1954, to the date on which the new service had to begin, to mount programmes capable of challenging the mighty BBC.

They began with temporary make-shift offices. The top men of Associated-Rediffusion found themselves housed in six offices in Stratton House, Piccadilly — comfortable enough to begin with; but a bit overcrowded when recruiting boosted the staff to 60!

The ATV backroom boys found refuge at York House, Bloomsbury and Regent House, Lower Regent Street. Here things were so cramped, according to Keith Rogers, then head of Outside Broadcasts, “that we all had to sit on the corners of chairs — in my room, for instance, there were four of us and masses and masses of files and correspondence.”

There was even a shortage of elementary office equipment. When Captain Tom Brownrigg arrived to take up his duties as general manager of Associated-Rediffusion, “I found myself with a nice office but only a table and a chair. So I had to go and find a telephone. Then a secretary. Then I went for a walk up Tottenham Court Road and bought a second-hand desk for £65.”

Lloyd Williams, then assistant Controller of Programmes for Associated-Rediffusion, recalled that conditions in Stratton House grew chaotic.

“There were never enough chairs — you just had to walk about the other offices and pinch what you could. Most of the time was taken up interviewing the prospective staff — after all, we had to hire something in the region of 600 people, right from scratch. Things got so bad that you never got a chance to leave the office.”

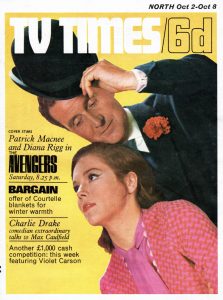

ITN, housed in Ingersoll House, Kingsway, had no complaints about space. But Max Caulfield, the chief news editor and Bill Sweeney, the chief engineer, fighting to get their departments organised, found themselves squabbling over priority for the only telephone in the vast office. Sweeney complained one day: “If I can’t use that telephone, we won’t be able to put out a programme!” Caulfield retorted: “If I can’t use it, there’ll be no programme to put out!”

The big task for all the companies was to find suitable premises and recruit skilled staff. As early as the frosty weeks before Christmas, 1954, Commander E. N. Haines, Managing Director of Central Rediffusion, the company providing technical services to Associated-Rediffusion, was tramping round London looking at possible studio sites.

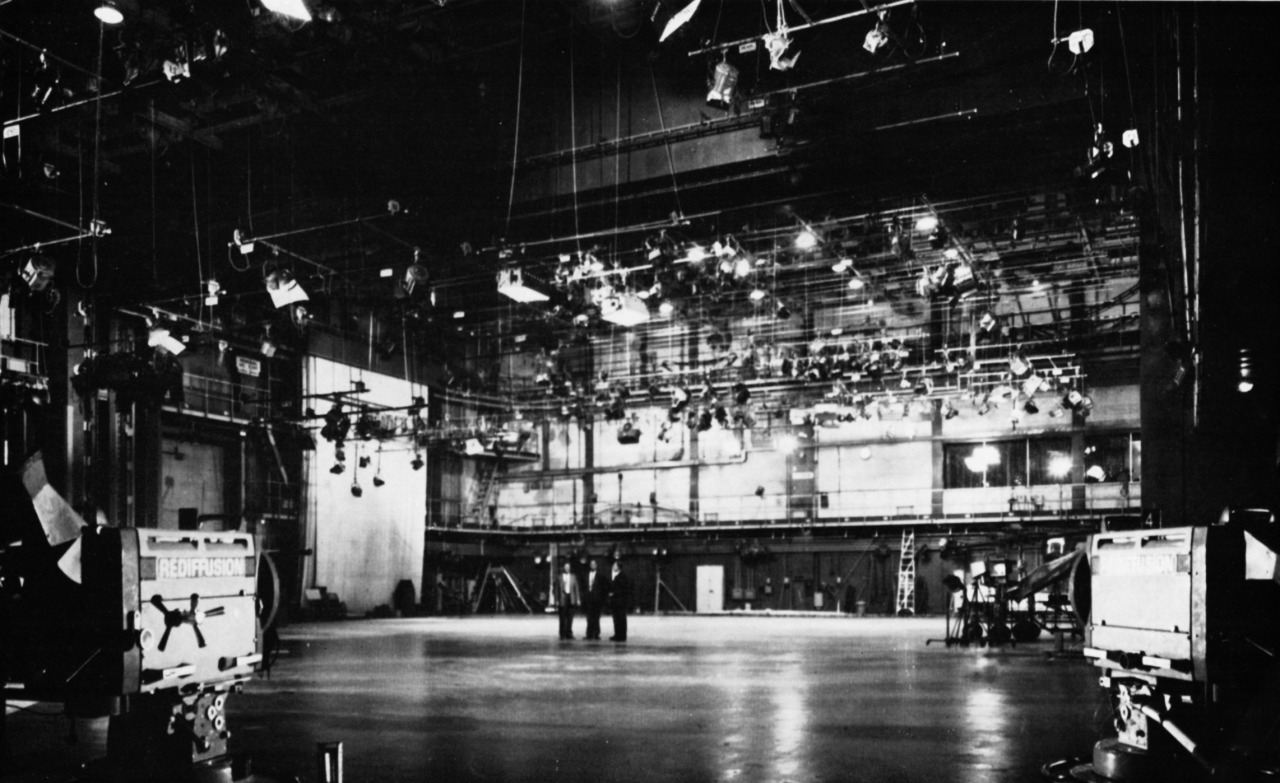

The choice eventually fell on the old Twentieth Century-Fox studios at Wembley. “Studios” was hardly the right word — there was only one big studio. And Haines needed at least four.

Worse, right in the middle of the studio was a big tank filled with thousands of gallons of water and a battered-looking old motor torpedo boat, laden down with film actors. Film-makers were still shooting a film called, “The Ship that Died of Shame.”

“We had builders and installing engineers in the same night the filming finished,” said Haines. “The ship was quickly unrigged and the tank emptied. Then we started building the four studios.

“The real problem was dust. We had only eight months from scratch to get everything ready and the trouble with rushing a job like this is that you are inclined to get technicians and gear in place before the place is dust-free and that can create an awful lot of trouble.

“We had plasterers working alongside installing engineers and the dust continually created problems we had to overcome somehow. A speck of dust lodged in the wrong place might well have meant no programmes on opening night.”

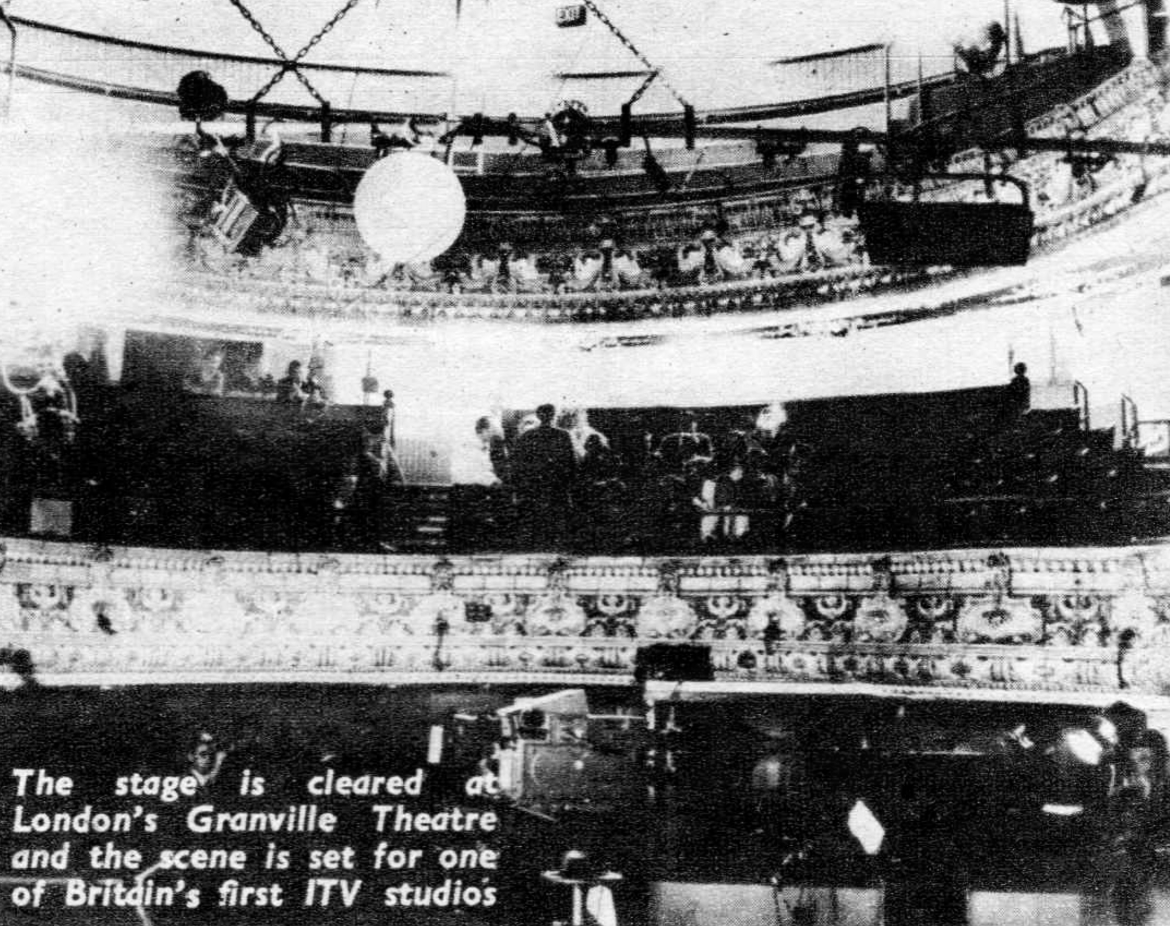

Associated-Rediffusion also bought the old Granville Theatre in Fulham Road as studios — which meant taking the whole theatre to pieces, turning the stage around, tearing out the old dressing rooms and redesigning everything to TV studio specifications.

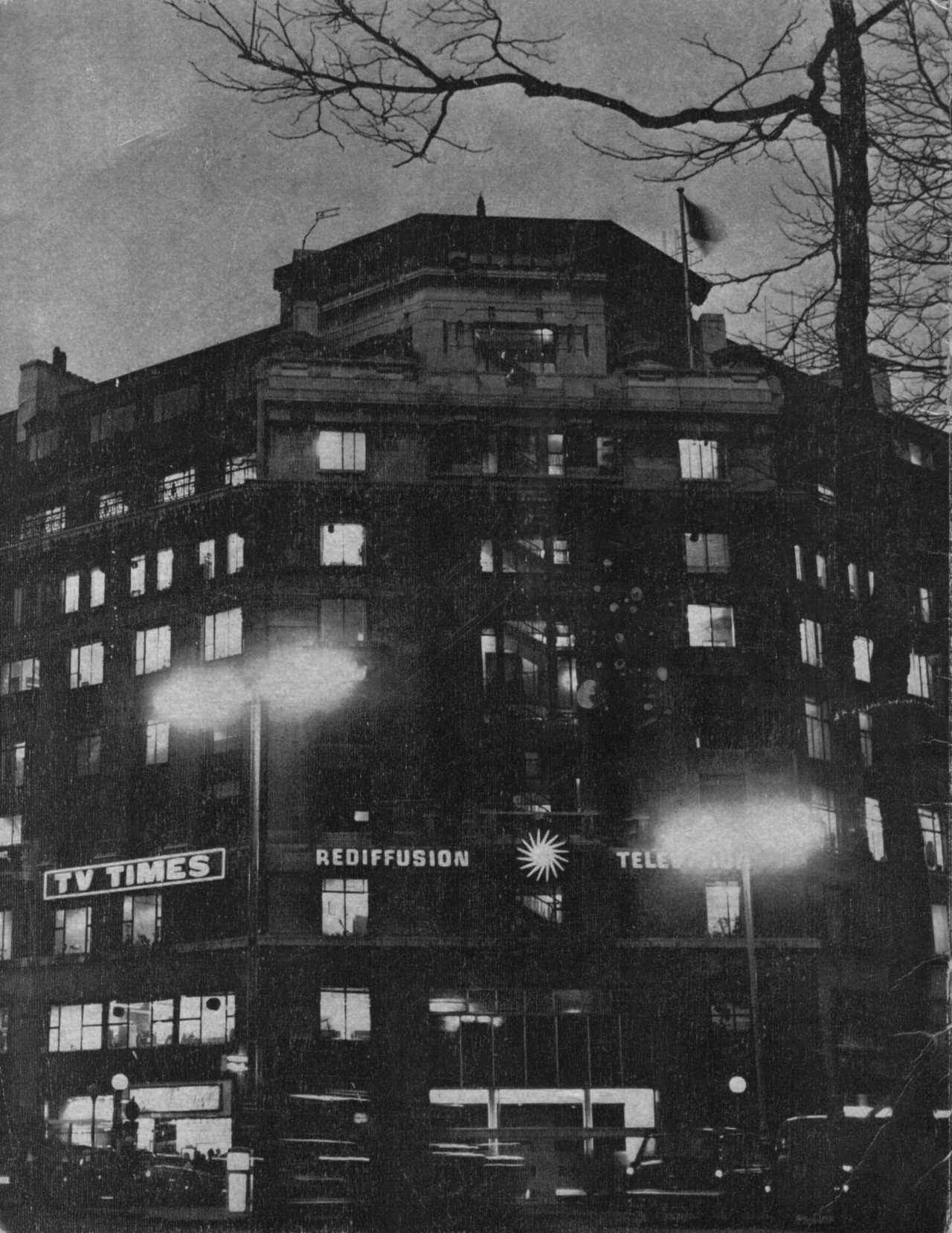

But the real nail-biting problems centred round Adastral House in Kingsway, the giant rabbit-warren of out-of-date offices from which the air war against Germany had been directed.

Although a 50-year lease was taken out in January, the company were unable to get in until the Air Ministry moved out — which was not until late in May. Then the gigantic job of tearing the whole place asunder and redesigning it began.

ATV, with only the weekend programmes to worry about (their transmission in the Midlands did not begin until the following spring) were able to manage in London with one big studio, the old Wood Green Empire in North London and a smaller studio and master control room in Foley Street, near the G.P.O.’s Museum Exchange, through which all TV lines pass to the transmitters. For office space, they hired two floors in Television House.

“My overriding memory of the very early days,” said Keith Rogers, “is of a small group of us. Bill Ward, then Head of Light Entertainment, now Executive Controller, Elstree Studios, his deputy, Frank Beale, Terence MacNamara. the chief engineer, and myself, sitting on the floor of an office in Regent House in the evenings, plans for studios and equipment scattered all around us, trying to work out exactly what were our requirements.

“We needed a complete outside broadcast set-up, with two or three O.B. vans, fully equipped. We required a control room, equipped with telecine, sound and vision mixing and also a full-sized studio (we got Wood Green) where we could stage variety and light entertainment programmes.

“We weren’t given a budget. We simply worked out what we needed and sent up the list to the directors. The most sobering thought for all of us was that when we totted up what we’d ordered after an evening’s work, we’d find we’d spent perhaps £500,000.”

By July, the job still seemed an impossible one. Skilled television technicians were at a premium. Men, of course, were being lured away from the BBC by prospects of promotion and better pay.

“But,” said Bill Ward, “not everybody was prepared to take the risk like we were. The directors of ITV companies risked losing their money if the new venture failed. And those of us who left the BBC knew that ITV simply had to succeed. If it failed, there was no going back — the BBC had made it plain they wouldn’t take us back. We knew we’d all be out of work.”

But, nevertheless, staffs slowly grew. Men like Presentation Officer Cyril Francis quit a job in commercial insurance to join; Neil Bramson gave up a career as a professional French-horn player with a leading orchestra. Muriel Young gave up acting to become an announcer. Chris Chataway chucked a safe job with a big brewery concern to become a newscaster with ITN.

In July, staffs at last moved into Adastral House, by then renamed Television House. Few offices were ready for occupation. Pneumatic drills thundered everywhere; barrow loads of cement were trundled up and down; dust fell in showers. Women employees were given a hairdressing allowance; the men were told to have their suits cleaned once a month at company expense.