THE small group of top executives sat numb and horrified. With only 24 hours to go before Independent Television opened on the night of September 22, 1955, they faced disaster.

At Television House, Kingsway and in the studios at Wembley where they crouched behind the computer-like machines which control the transmission of programmes, they stared white-faced at the monitor screens in front of them.

All were — catastrophically — blank. The final run-through before ITV went on the air had failed.

This was the situation: Five Outside Broadcast cameras had been set up in London to transmit the opening night’s programme.

Early in the afternoon of September 21, the two men in charge of the master control units — Cyril Francis at Wembley and Neil Bramson in Television House — took their seats at their “space-age” desks.

They exchanged light hearted banter with the assistants and technicians around them which did nothing to relieve the underlying tension.

At approximately 3 p.m. they started the procedure for bringing all the OB points under their control.

“Cue Wood Green!”

Dutifully sound and vision ‘mixers’ threw their switches. On the bank of monitor screens, a picture from the Wood Green Empire should have come in loud and clear. Instead, nothing!

“Cue Shoreditch!”

Still nothing! Phone calls, frantic messages flashed out. Nobody could find out what was wrong. Then, after two hours of tense, sweating anxiety and frustration, the Programme Controller called off the rehearsal. “Not to worry, we’ll try again later.” At 6 p.m. they tried again. Once more Francis and Bramson sat tense and sweating in front of their monitor screens. Behind them, chiefs of the new service smoked incessantly and made little jokes and remarks.

“How are things going?” asked one of the top brass. “Ruddy awful!” replied Francis.

For a second it looked as if the earlier disaster was about to be repeated. Sound and vision had come in loud and clear from four OB points but the fifth still showed blank. Panic! But a swift phone call and suddenly the screen came alive.

Twenty-four hours before the new service was due to open, secretaries and technicians acted as ‘stand-ins’ for the distinguished people and well-known artists who would be seen the following evening.

On the big night, nerves were stretched as the 7.15 deadline neared. At 6.55 p.m. Cyril Francis took a deep breath, glanced round his tiny control room filled with anxious, straining faces, and checked his monitor screens. In Television House, 10 miles away, Bramson followed the same procedure.

Relief! — the pictures came through beautifully clear. Sound, too, was OK. Everybody kept their fingers crossed hoping that the gremlins had been locked out of the works. The Control Engineer felt a sense of marvellous relief. Then suddenly he stiffened. With less than five minutes to go, a monitor screen went blank!

With a feeling of panic, the Control Engineer lifted a phone and rang the G.P.O.’s Museum Exchange, through which all the TV lines are fed to the transmitters. “Has anybody touched anything?” he yelled.

A confused scramble at the other end, then a voice said: “We just pulled out a plug to check that it was OK.”

“Well, put the ruddy thing back at once!” yelled the irate Control Engineer. The blank screen flashed to life.

The first thing seen by viewers, watching 600,000 converted sets in the London area and waiting tensely for the big switch-on, was a black cross on a white ground, accompanied by a high pitched scream. For a moment many must have thought things had gone wrong.

Then the legend “Opening Night Independent Television Service Channel 9” flashed on the screen and the voice of Leslie Mitchell, the veteran broadcaster, declared: “This is London!”

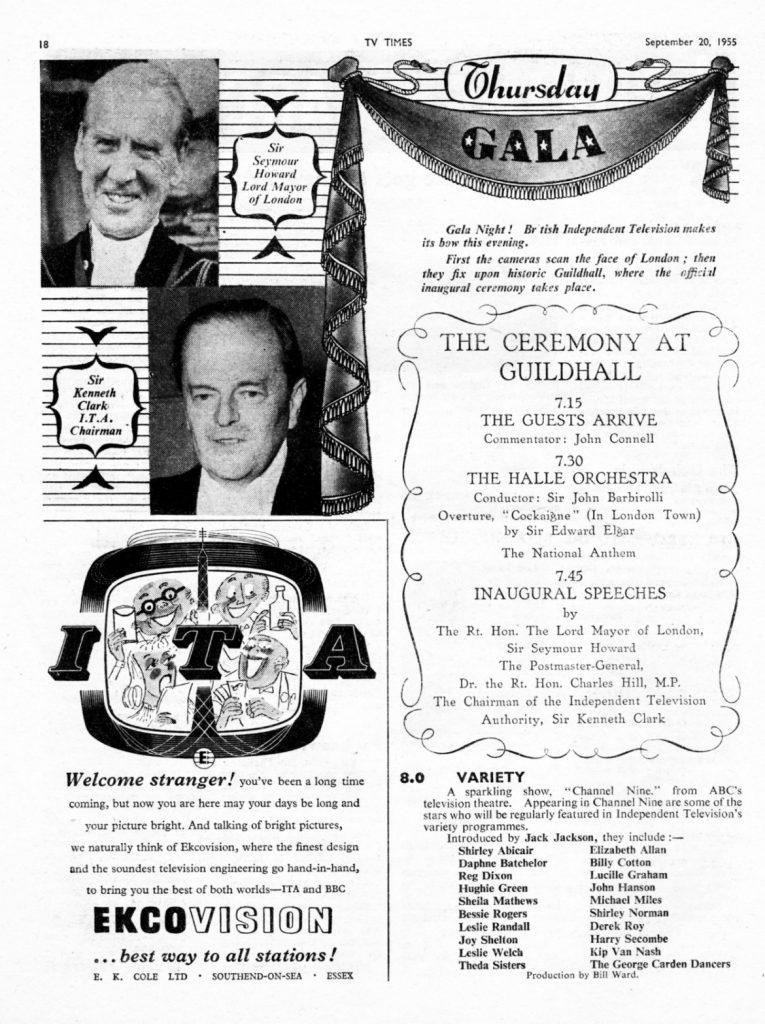

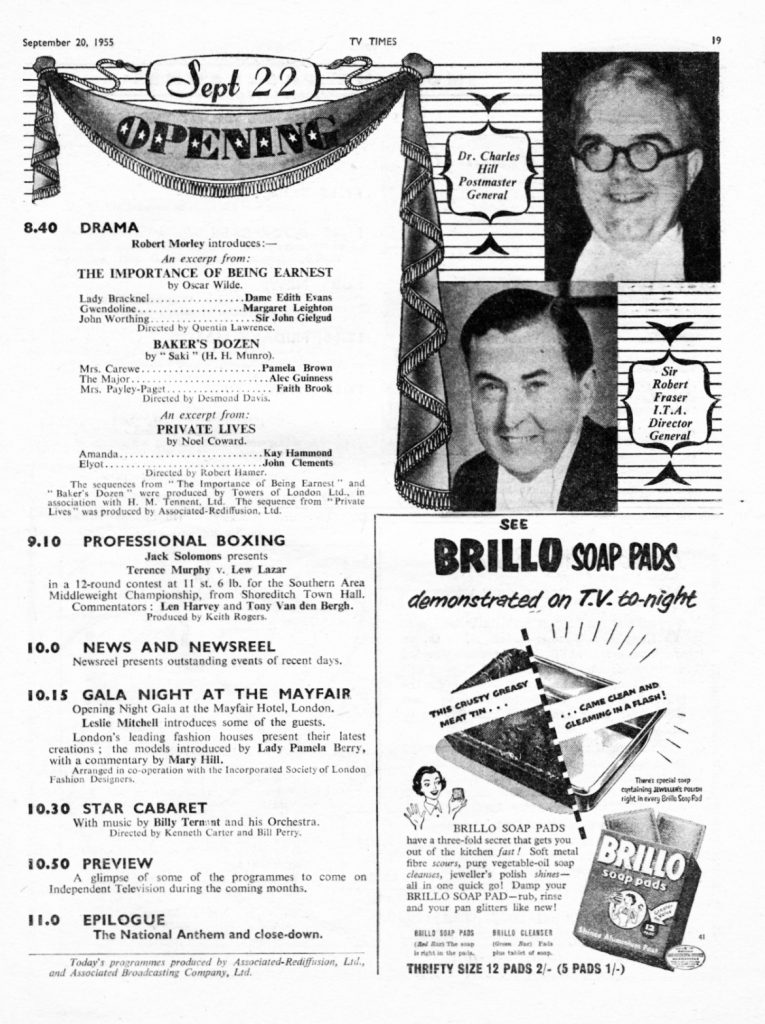

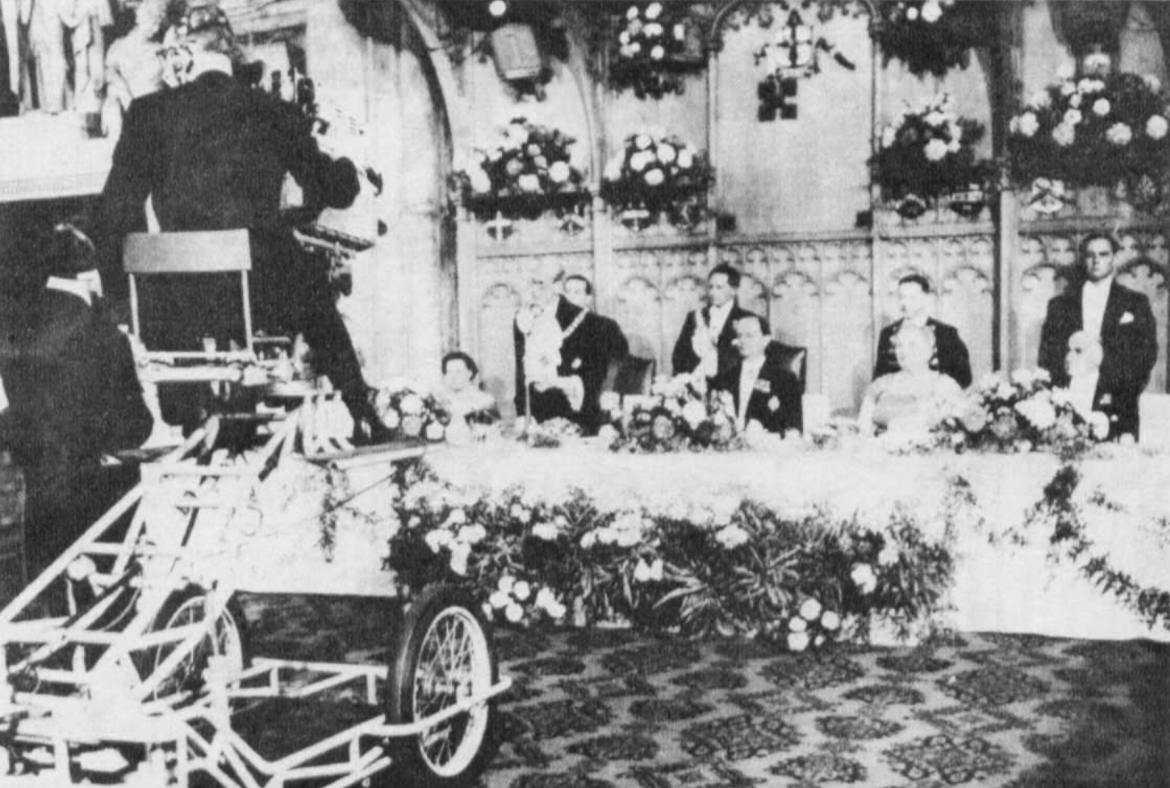

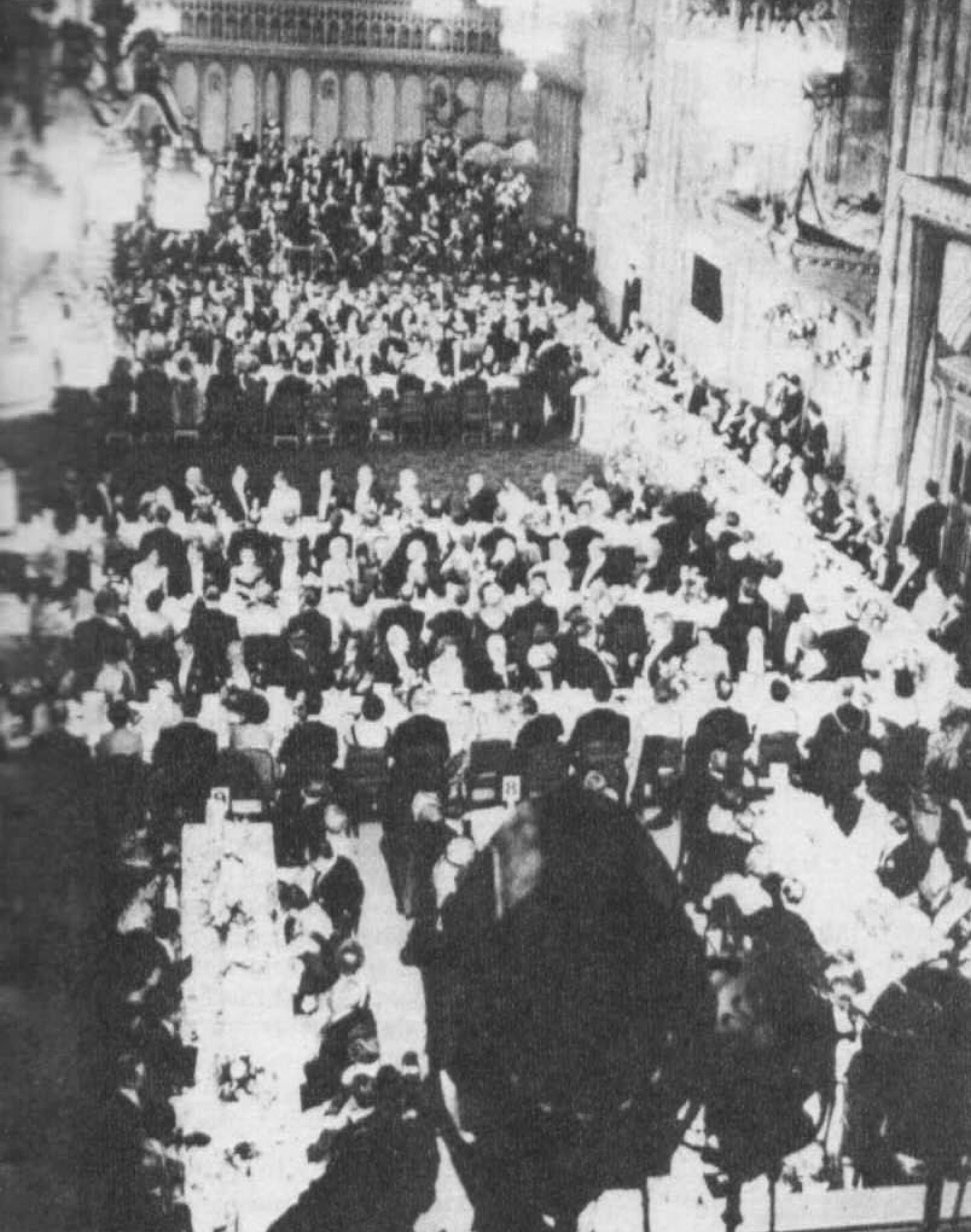

A brief snatch of film, with the commentator saying: “Wish us Godspeed. Over to Guildhall. Take it away, master control!” And suddenly viewers were with the 450 distinguished guests — who included the Postmaster General, Dr. Charles (now Lord) Hill, now chairman of the ITA, Sir Kenneth Clark, then ITA chairman, and the Director-General, Sir Robert Fraser — listening to the Hallé Orchestra at ITV’s inaugural banquet in the historic Guildhall. Independent Television was born!

It was 8.13 p.m. before viewers saw what they had been waiting for — the little items that were entirely new to British audiences. The commercials.

The first commercial in British history was for Gibbs SR and showed a toothbrush and a block of ice. The second was for Cadbury’s drinking chocolate, and the third for Summer County margarine.

Altogether viewers saw 24 advertising ’spots’ during the evening and found them fascinating. Within a week, people all over London were whistling TV jingles instead of the latest popular tune.

A variety show, starring Harry Secombe and Hughie Green among others; drama excerpts introduced by Robert Morley; a professional boxing match; a visit to the gala opening night with cabaret at the May Fair Hotel; the news (read by champion runner Chris Chataway) and ITV closed down its first night’s programmes.

The Press next day was kind if not over-enthusiastic. But on one thing they were all agreed — all the prophecies and warnings that it would take two years at least to mount a new television service had been wrong. It had been done successfully in ten months and technically everything had been perfect.

Yet although everything appeared to go off without a hitch, there were at least four ‘mishaps’ during the evening. Viewers saw two of them but missed the other two.

The first one they didn’t see took place in the Guildhall. The Hallé Orchestra, having finished Elgar’s ’Cockaigne’ suite, rose from their seats and attempted to leave the rostrum only to find that they were trapped.

So hemmed in were they by tables, guests and TV equipment that they had to sit where they were until the banquet and the speeches had finished.

The second took place in the offices and studio of ITN. Minutes before the news at 10 p.m., Chris Chataway snatched up the prepared bulletin and raced out to the lift that would take him up seven floors to the ITN studio on top of TV House. He found the lift jammed!

“It was a terrible moment,” says Chataway today. “We were all in a desperate state of anxiety and excitement — and then this. Fortunately my limbs were still in a sound state in those days and I raced up the stairs two at a time, followed by the whole production staff, puffing and blowing for all they were worth.”

Another hitch — which viewers actually did see — also involved Chataway. He had begun his first newscast and everything was going fine when he found that the teleprompter on which his script was revolving was going too slowly. It was being operated by a secretary who could control its speed with a gentle pressure of her foot.

Chataway began slowing down to keep pace with the machine — only to find to his horror that the slower he went, the slower the teleprompter revolved!

Finally, in desperation, he risked glancing away from the camera to look round at the girl who was standing a little behind him and out of vision. She realised her mistake immediately and at once speeded up.

But next day a critic wrote: “Mr. Chataway did fine except for one moment when he glanced over his shoulder, apparently to see where the rest of the field were.”

The second hitch which viewers saw was certainly far more hilarious. At the end of each round of the professional boxing match from Shoreditch, there was a break for commercials.

At the end of one round, the director cut away from the ringside to show a half-minute of advertising.

The last of these ‘spots’ was for a well-known beer. Viewers saw the bottle of beer, watched it being poured into a glass and finally saw a man drinking it with obvious satisfaction. Just at that moment the director cut back to the boxing. The boxer, on whom the camera focused, having rinsed out his mouth, spat the water into a bucket. The impression given was that he was spitting out the beer!