THE pace grew faster as the deadline approached September 1955, opening night for ITV. In the haste, clashes between unions and management were inevitable.

At Shepperton Studios, filming of a series of one hour dramas stopped when it was found that a director was not a union member. Then the Musicians’ Union threatened a strike over pay.

Camera operators struck a few days before opening night, and in ITN all “dummy runs” came to a temporary halt.

Conscious of the slogan “Never Baffled” he had given ten company, Captain Tom Brownrigg, General Manager at Associated-Rediffusion, (now Rediffusion), quickly sorted the problems.

The unions were as anxious as anyone to make sure everything went well. They had a big stake in Independent Television.

Despite the difficulties, a wide variety of programmes was being prepared. Drama producer Cyril Coke began working with the late Macdonald Daly, the dog expert, on a series of pets programmes that proved to be among the most popular of ITV’s earlier shows.

Transatlantic favourites such as I Love Lucy and Dragnet were bought; the Grade organisation searched the world for top talent for the new variety spectaculars.

Orson Welles went round the world for ITV, taking a personal look at its problems and its pleasures.

Suddenly, it was opening night…

Despite the glittering success of that night, ITV’s troubles were just beginning.

“The following day every thing seemed to go wrong,” said Neil Bramson, who was in charge of the master control.

“We were still operating with much temporary equipment because the manufacturers had not been able to deliver everything in time. And there were gremlins.”

Things were not eased for Cyril Coke when Customs refused to allow Orson Welles to bring in a film of his travels. He turned up at the studio with a substitute unedited and without commentary.

“We simply can’t do it.” said Coke.

“Don’t worry, son,” replied Welles grandly. “You roll the cameras and I’ll talk as we go along.”

“But the timing!” protested Coke. “I’ve got to bring the commercials in on time!”

“Never you worry, son! We’ll manage it.”

It could be done but it couldn’t be done in time. Welles was still giving voice to his commentary when Coke had to cut him off.

Welles stormed out, threatening never to work for ITV again.

Compere Leslie Mitchell said: “One basic trouble was that many of our staff were inexperienced. One young producer, handling his first programme, suddenly froze in his seat and could neither move nor speak.

“Everything was going haywire when I woke up to what was happening. ‘Cue two!’ I yelled (‘cue camera number two’). He responded and the programme was saved.”

ITV’s troubles in those early days went much higher. Suddenly it was facing a financial crisis.

People were slow to convert their sets to receive ITV programmes and, with only two companies to take the initial strain of the heavy capital and running costs, losses mounted.

“I had forecast to my fellow directors that we must be prepared to take losses of at least £3 million before Independent Television was likely to begin making a profit,” said Paul Adorian, managing director of Associated-Rediffusion.

“Those of us who had faith were rewarded eventually.” Captain Tom Brownrigg said: “We had lost £3$ million and looked like losing more.

“A firm of advertisers came to me and said: ‘Look, we’ve got a successful show running in America which we sponsor there. If you let us put it on here, we’ll guarantee to buy a;l the spots surrounding it.’

“’No,’ I told them. ‘If I did that, I’d be allowing sponsored television.’

“Then, a big company came along with a proposition which would have turned the tide earlier. They wanted a pattern of broadcasting which meant giving over almost an entire evening’s commercials to their products.

“’We’ll pay you £1½ million,’ they said. ‘Your sales chaps have sold some of this time to a few little advertisers — so you’ll just have to tell them their time is cancelled.’

“’You mean, I’d have to break faith with some small advertisers to accommodate you,’ I said. ‘Well, I’m sorry!’ And so I let them walk away with that £1½ million.”

The faith of Adorian and the courage of Brownrigg were rewarded.

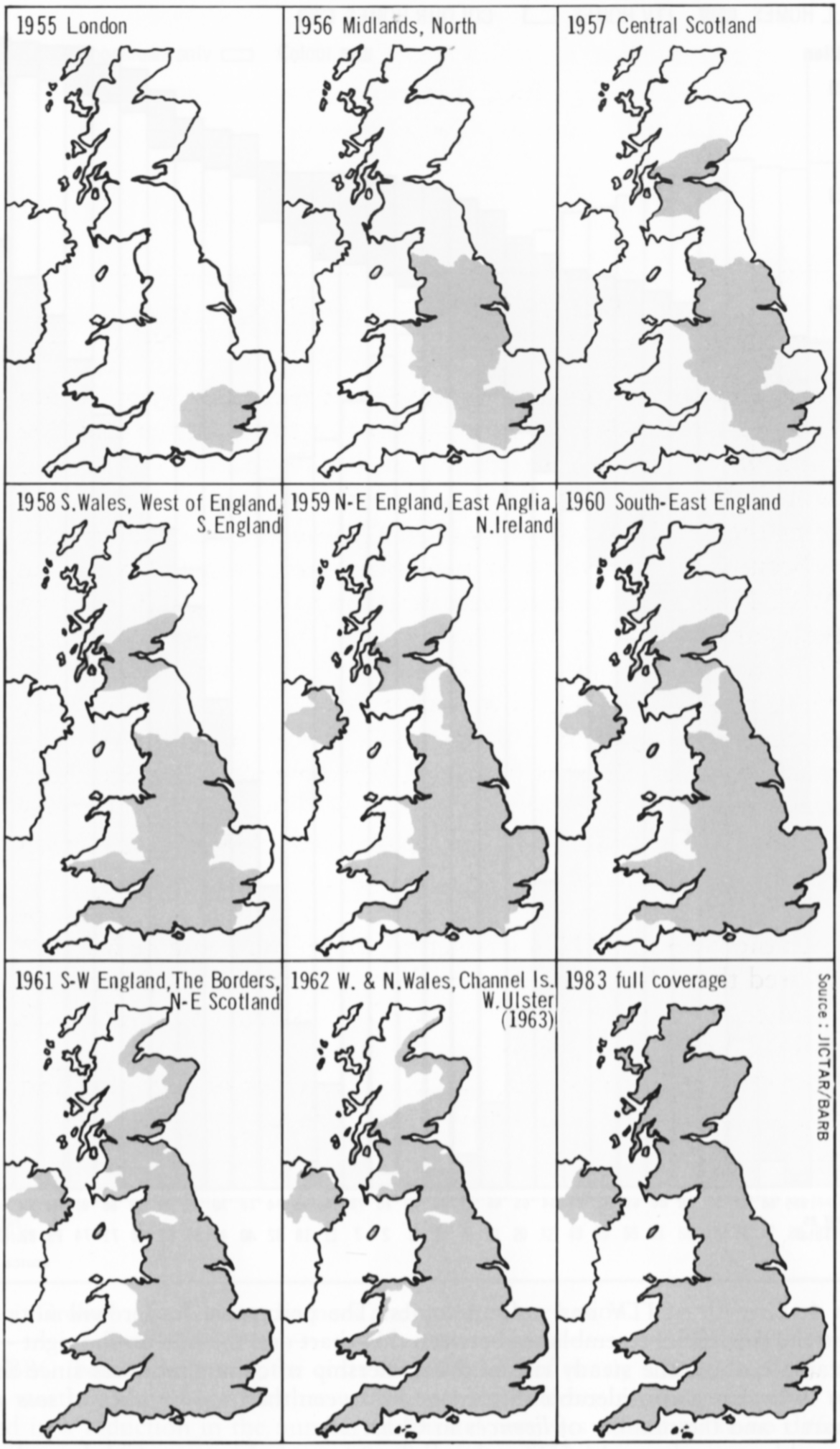

As other companies sprouted and ITV transmitters began to beam their programmes over a wide area of Britain, more advertising revenue flowed in.

The costs of making programmes and operating studios began to be spread over the growing number of companies. Within three years ITV had turned the tide.

The stage was set for the time when there would be 14 programme companies giving 97 per cent. of the population alternative programmes to the BBC.

So ends the beginning of the ITV story.